Seven Lessons Learned from South Korea’s Response to COVID-19

As the coronavirus hits Europe and North America, it appears as though people are responding in two drastic ways: panic or indifference. In the U.S., stores all across the country are lacking supplies. Panicking customers have bought out toilet paper, masks, anti-bacteria gel, over the counter medications, and even non-nutritious snacks. Grocery stores have had to put a limit on how many toilet paper packages an individual customer can buy. Masks and hand sanitizer are practically non-existent and not able to be purchased.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the spectrum, others are ignoring the urgency of COVID-19 almost completely. Few people are wearing masks in public. Pictures on Facebook still indicate that people are traveling, vacationing, and living their lives like normal. Hospitals are not handing out masks, as they have no extras, and the most vulnerable in society, the sick and immune-compromised patients, are at risk of exposure to a highly contagious disease. Even doctors have insufficient supplies and protection against the virus, lending not only themselves vulnerable to contracting COVID-19 but also the patients whom they treat.

My concern is that both of these responses are not helping contain the pandemic. Although I am not an expert in infectious diseases, my personal experience with the outbreak in Korea gives me some insight from which those in the West can benefit. The approach to the coronavirus has been significantly different in Asia, particularly in South Korea. The governmental systems of China, Mongolia, and North Korea are in stark contrast to democracy in the United States. As these countries have responded, we cannot expect America to shut down its borders, lock down its cities, or quarantine every traveler entering the country.

But South Korea provides a good example of what is possible if a democratic government is proactive about containing the virus. South Korea early on became the number two nation for the outbreak, but thanks to the country’s quick response, it has now dropped to number eight. From my personal experience of living through the pandemic here in Korea, I can pinpoint key, critical responses that were taken and, as a result, largely responsible for the relatively quick viral containment in the country.

Typical COVID-19 Precautions in South Korea

1. Shut down of all public gatherings and events.

As soon as one large religious gathering became responsible for the vast majority of COVID-19 cases increasing in South Korea, all public events and gatherings were cancelled. Schools were already on winter break, but the resuming of the spring semester was immediately postponed. This included daycares, preschools, extra-curricular activities, as well as all public and private schools. College and universities transitioned to online education, and all sporting events were cancelled. Church services for almost the entire country were cancelled, and all special events and occasions were either cancelled or postponed. This significantly reduced the speed and spread of viral transmission.

Although this is one area that the United States is excelling in, it is only the first step of many.

2. Country-wide use of masks and ethanol.

South Koreans were already accustomed to wearing masks, especially in cold, winter months. Many choose to wear masks to protect themselves from the cold, whereas others are in the custom of wearing disposable masks due to occasional problems with air pollution and yellow dust. As a result, masks were never in short supply. The general public starting wearing masks on a regular basis to protect themselves from the disease even before it hit South Korea’s border.

Even still, the South Korean government ensured masks for every citizen. Many cities, like our own, handed out free masks to each household. Then, the government assigned both stores and specific dates for buying masks. Only certain stores in a particular area would sell masks to individuals based upon their birthdates. People lined up and waited for 45 minutes to an hour to show their country registration number and prove that it was their turn according to their birthdate to obtain masks at the cost of approximately $5 U.S. dollars.

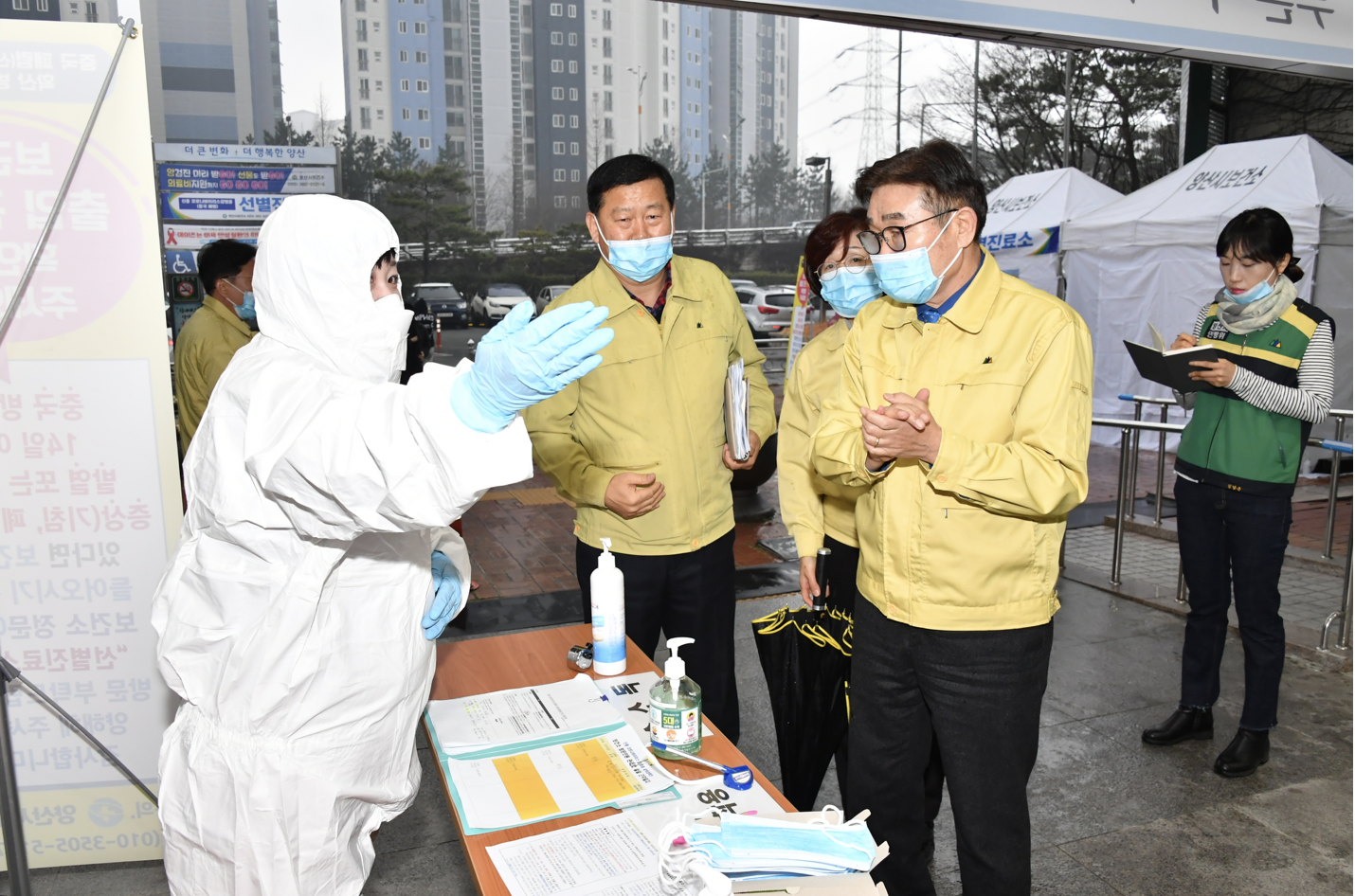

Most public buildings mandated the use of masks. Containers of anti-bacterial gel were placed at the entrance of buildings for individuals to sanitize their hands before entering as each person was expected to carry and put on their own mask. Hospitals took this one step further. If someone entering the hospital did not have a mask, they would provide one for you. Medical personnel in triage tents screened each patient and family member entering all medical facilities before anyone was allowed through the front doors. In addition to these precautionary measures, body temperatures were also scanned by medical staff before entering.

Some experts have advised that only those infected with the virus need to wear masks. Since COVID-19 is transmitted through body fluids or airborne water droplets, as long as the individual coughing and sneezing is masked, they assume the virus will be contained.

However, that is just not the case. The average person touches their face about 23 times an hour. And since the virus can live on surfaces for up to 5 to 7 days, that means every time a person who is contagious touches his or her face and then a doorknob or a chair or any surface, then they can infect multiple other people. All the time this person who is contagious can be unaware of the fact that he or she is carrying COVID-19. The coronavirus can be latent for up to 14-21 days, meaning that individuals can be carrying the virus and contagious for up to two to three weeks before showing any symptoms. Masks prevent not only the spread of the disease from sick individuals but also containment from individuals who are not yet aware that they are carriers of the virus.

Thus, one other practice in South Korea has also been wiping down doorknobs, table surfaces, backs of chairs, and any commonly touched surface with ethanol. In addition to anti-bacterial gel for hands and masks for mouths and noses, spray bottles with ethanol are also commonly placed at entrances and used to sterilize public buildings.

3. Proactive tracking down of people exposed to the disease.

Once an individual was tested positive for the coronavirus, the South Korean public health department was very aggressive in tracking down each person that could have been exposed to the disease. The government used all resources available to them, including CCTV and cell phone data. Once a person was confirmed having COVID-19, each person they met, each place they visited was investigated. In the event that a potential person exposed to the virus could not be located, public announcements were issued. An announcement would say something to this regard, “If you were at the corner of 3rd and 4th Street between 4 -4:30 p.m. on Wednesday March 8th, contact the health department immediately. You could have been exposed to COVID-19.”

But most of the time, the individual was readily identified, and as a result, they would immediately receive a text or phone call from the public health department. The text would say something like this, “Come immediately in to be tested for COVID-19. You have been identified as a person who has potentially been exposed to the virus. Do not travel or go anywhere else. Come immediately to the hospital.”

In this way, almost all carriers of the disease were quickly identified. They were tested and quarantined according to results to prevent further spread of the virus.

4. Rapid screening and testing.

Because of South Korea’s incredibly aggressive approach to tracking down COVID-19, mass numbers of people were tested for the virus. South Korea developed a test kit that allowed for rapid results. Individuals could know within 2-6 hours whether or not they tested positive. Until results were verified, potential patients were kept in quarantine. If the results were negative, individuals were free to leave. If they were positive, patients immediately received treatment.

5. Early intervention and treatment.

Again, each person that potentially could have been exposed to the virus was literally tracked down and tested. Therefore, the number of coronavirus cases were high in comparison to the death rate. This is because early detection allowed for the testing of mild cases as well as moderate to severe cases. Data for all positive cases for COVID-19, even those that may not display symptoms, kept the death rate for the disease extremely low. Mass testing also allowed for early intervention, which provided respiratory assistance to patients sooner rather than later. Early treatment was also a significant contribution to the low death rate in South Korea.

6. Transparency of the number of cases.

Every day the number of cases were posted and updated on several websites. This was live COVID-19 tracking for the country. But it was not just the number of cases, deaths, and recoveries that were posted. The number of people being tested each day was also posted.

We knew that the virus was being contained when the number of people being tested each day started to drop. This number still continues to drop slowly every day. However, this number was initially very high. In fact, this number in South Korea is still currently in the tens of thousands. But a high number is a good sign because it indicates that the public health department is seeking out, finding, and testing many of the individuals that were exposed to the virus. It was clear that those contagious were being contained to prevent further transmission of COVID-19 throughout the country.

As the cases in South Korea plateaus, the number of individuals being tested is declining and will continue to decline. Eventually, there will be no more cases left to test.

7. Public awareness and cooperation.

South Korea has an excellent emergency alert system. Even before COVID-19, cautions for weather, health, and other general concerns are routinely texted as alerts on all cell phones. The system is much like the amber alert system in the United States.

Throughout the coronavirus outbreak in Korea, alerts came through all cell phones on a daily basis. The general public was well informed of key prevention practices as well as kept informed of the number of cases in their area.

But I personally think that public cooperation was particularly critical. Asian culture, in general, is more collectivistic in their thinking compared to Western, individualist mindsets. This aspect of culture can have its downsides, but in this case, I think it was a key asset to viral containment.

When the city of Daegu started to spike in COVID-19 cases, surrounding cities and provinces immediately responded in a like manner. In my own small city, there has yet to be a single case of coronavirus. However, just like the rest of the country, the city decided to postpone the opening of schools, cancel all public gatherings, and provide masks and hand sanitizer for all households.

In the beginning, some people began to panic, but that was quickly abated. People soon became accustomed to wearing masks out in public and washing their hands frequently. If individuals did not want to risk going to the grocery store, they simply shopped online. Necessities were delivered to your door instead of going out in public.

In general, people were calm yet wise. We simply chose not to meet in large groups. We took precautions by sterilizing surfaces, sanitizing hands, and protecting our faces. And although it has been inconvenient having children home and schools today are still not in session, most of us in South Korea are grateful to be healthy. We see how the virus is spreading across the globe, and we are thankful for the ways South Korea has been proactive about containing the pandemic. Despite the inconveniences and isolation caused by preventive measures, we now see that South Korea is a model for how other countries can response to COVID-19.